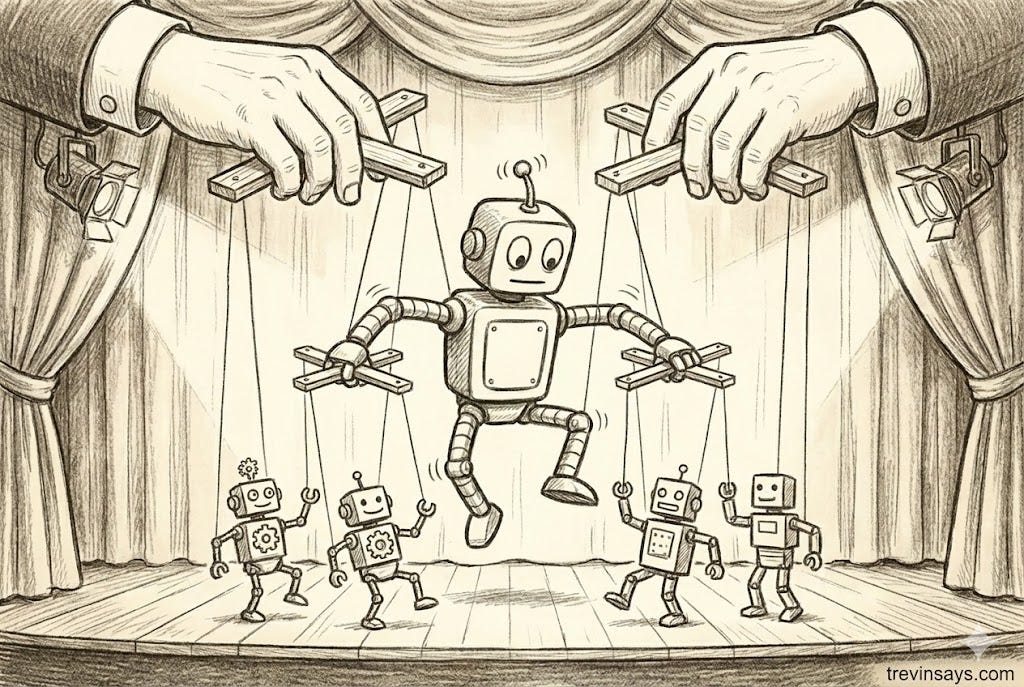

2026: The Year of Agent Orchestration

Why the next wave of AI gains will come from coordination, not capability

A year ago, people were still questioning whether AI could do basic math. Now we’re questioning whether we can keep up with systems that work faster, longer, and in parallel. The bottleneck has flipped, and it flipped faster than most people want to admit.

The capability is there in the foundational models, but what’s missing is the orchestration layer that makes it usable at scale. In 2026, a lot of money and attention is going to pour into orchestration and observability, first in developer tooling and then throughout roles in the rest of the organization. We will watch IDEs evolve into agent control centers, and then watch those patterns spread into product, design, marketing, operations and anywhere else work is complex and interdependent.

The teams who figure out orchestration will unlock productivity gains that make “10x engineer” sound quaint. Not because engineers suddenly become superheroes, but because the unit of work stops being a single person’s output. It becomes a coordinated system.

The bottleneck has flipped

Recently, I recently had 4 Claude Code instances working in parallel on related parts of a side project I’m working on. Each agent’s work was scoped carefully to minimize overlap while still being cohesive enough to merge. They finished over a 35-minute period.

Then I spent 25 minutes managing merge conflicts, which is a fun reminder that the agents did the hard part and I did the part nobody wants to.

I could have picked three unrelated areas and avoided most of the integration pain, but that is not how real work flows. Related problems need related solutions. Once you are operating in a single codebase, work entangles. When agents become capable enough to move quickly inside that entanglement, integration becomes the constraint. This is no different than humans working in the same codebase, it’s just the agents are able to work 24x7.

This crazy part is how quickly this has evolved from being a model problem into one of coordination.

In a remarkably short time, we have gotten MCP servers, agent systems, skills frameworks, and exponentially improving foundational models. For most situations, individual task capability is not the limiting factor anymore. The challenge has shifted toward multiplying yourself across many work streams simultaneously while keeping the work coherent.

Skeptics will look at orchestration friction and say it proves AI isn’t as capable as proponents claim. The opposite is true. Merge conflicts do not exist because the agents are failing. They exist because the agents are succeeding fast enough that human coordination becomes the bottleneck. A year ago, we would not have had multiple meaningful changes worth merging in the first place.

The struggle has moved up the value chain.

Where orchestration will emerge first

We’ve been conditioned to think of IDEs as places to write code, debug code, and browse repositories. That mental model is already outdated. Tools like Cursor expanded what an IDE does by putting agents at the center, but we are still in the messy part.

The IDE of the near future will not primarily be about writing code. It will be about spinning up and controlling agents, giving them direction and context, auditing what they’ve done, and maintaining observability into parallel workstreams. Today, most agent workflows still collapse down into terminal transcripts. That interface works when there is one thread of work. It breaks down when work becomes parallel and interdependent.

Josh Puckett captured the interface problem perfectly:

This hits because not only did I grow up playing real-time strategy games, but they also inherently tackled the “coordinate many parallel workers” interface problem decades ago. They make ownership, progress, dependencies, and collisions visible. As much as I adore Claude Code and the terminal, it simply isn’t a control plane. We suffer with an inability to effectively know what agents are working on, how they intersect or how tasks relate. Once you are running even a handful of agents, you need to see the whole board.

This is why orchestration becomes inseparable from observability. Observability means you can answer, quickly and confidently, what each agent is doing, what it touched, what it assumed, what it produced, and what it is about to break. Without that, you are not orchestrating a system, you’re along for the ride (and likely in denial).

Signals that the market is already forming

The best evidence that orchestration matters is that developers are already building it for themselves. Tools are showing up because the pain is immediate and the constraint is obvious.

Steve Yegge’s “Gas Town” essay is one of the clearest articulations of the new frontier:

“I went to senior folks at companies like Temporal and Anthropic, telling them they should build an agent orchestrator, that Claude Code is just a building block, and it’s going to be all about AI workflows and ‘Kubernetes for agents’. …

‘It will have a Merge Queue,’ I said.

‘It will orchestrate workflows,’ I said.

‘It will have plugins and quality gates,’ I said.

…

So in August I started building my own orchestrator, since nobody else seemed to care.”

That quote matters because it is not a vague prediction. It names the primitives you inevitably need once work becomes parallel: merge queues, supervision layers, workflows, plugins, and quality gates. It also captures the adoption gap. Most developers are still using a single agent as an enhanced copilot. The frontier is already thinking in terms of swarms, supervision, and reliable pipelines.

Other tools and projects are emerging for the same reason. Conductor is a great example and one of my new favorite tools. On the surface it appears to be a thin shin on top of Claude Code instances and Git worktrees. However, once you dig deeper, you appreciate all the clever things their team has done to make this a much better orchestrator than you first realize.

Other projects like Claude Squad, Claude Flow, and Auto Claude have also shown up because engineers have both the incentive and the ability to scratch their own itch.

This is not limited to developers. Workflow automation platforms are becoming the bridge that brings orchestration to technical teams outside engineering. n8n is a good example of what happens when orchestration gets packaged into something usable for people who understand their business problem but do not want to operate a developer stack.

Companies do not want “AI.” They want work to get done, reliably, without the whole thing turning into a science project where you’re lighting money on fire.

“The AI race isn’t only about smarter models. It’s about who can actually put that intelligence to work reliably, inside actual businesses.”

The velocity of change should recalibrate expectations again. The intelligence is compounding quickly which is forcing the bottleneck to shift to the systems that coordinate it.

The new math

We used to talk about 10x engineers. But when you can spin up multiple agents working in parallel, the math changes. Leverage is no longer limited by how fast you can type or how many hours you can work. It is limited by how many agents you can direct effectively across interconnected workstreams while keeping output coherent and integration cost low.

Over time, this also changes who can do technical work. As orchestration improves, more work that used to require deep engineering expertise will be done by product managers, designers, operations teams, and domain experts who understand the problem best, with agents handling execution. The boundaries between roles soften because the limiting factor becomes coordination and judgment, not implementation.

The individual agent capabilities are largely solved. What is missing is the layer that makes those capabilities composable, parallel, and reliable.

That is why 2026 looks like a real inflection point to me. Orchestration becomes the focus, and investment pours into the tools and interfaces that let humans direct multiple agents without losing coherence. As those patterns mature, they will spread beyond engineering into product, operations, and design through interfaces that look nothing like command lines.

2026 is the year the orchestration control plane becomes real.