Stop Thinking in Human Time

The economics of 'later' have changed

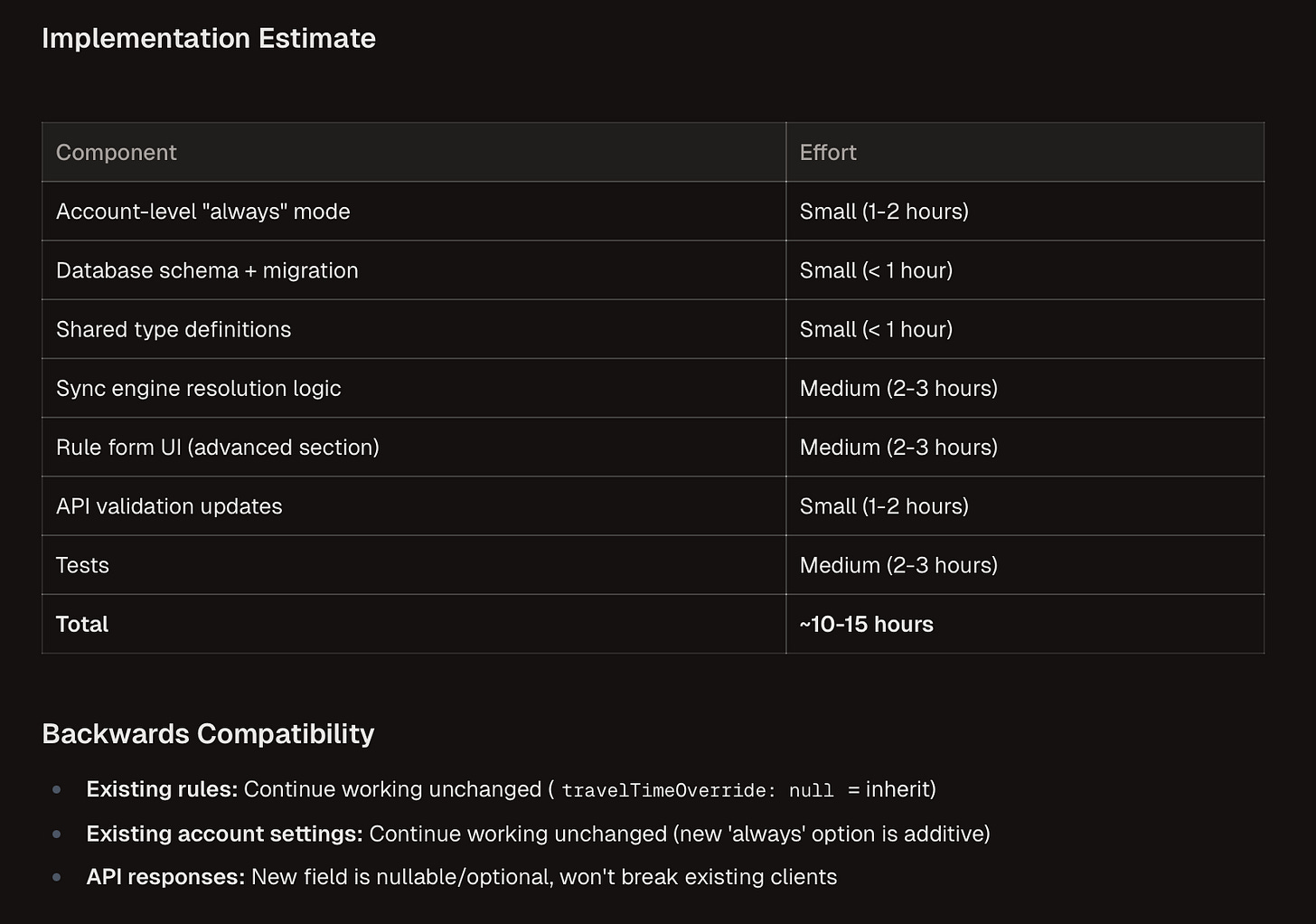

Last week, Claude Code was assessing the complexity of a new feature and it came back with a work breakdown and time estimate of “10-15 hours.”

Claude wasn’t wrong, exactly. It’s been trained on our documentation, our sprint retrospectives, our Linear tickets. It gave me back likely the same estimate a human would have given in a pre-AI era. But here’s the thing: the agent itself could do the work in about 15 minutes. It was estimating in human time because that’s what we’ve taught it to do.

We’ve spent decades calibrating our decisions around human labor constraints. Story points, t-shirt sizing, two-week sprints, “is the juice worth the squeeze?” All of it assumes that developer time is the scarce resource. With agents working in parallel while we sleep, that assumption is starting to look like an artifact of a world that no longer exists.

The hidden cost of “do it later”

When we defer work, we tell ourselves we’re saving time, but we’re actually transferring cost to our future selves (and others) in ways that compound.

There’s the coordination overhead of tracking the work item, writing up context for whoever picks it up later, the prioritization meetings to decide if “later” ever comes. There’s the context switching tax when someone else inherits the problem and has to reconstruct what the original author was thinking. And there’s the compounding risk as more code builds on top of the deferred issue, making it progressively harder to unwind.

The 2018 Stripe Developer Report found developers spend 33-42% of their time on rework, bug fixes, and maintenance. Southwest Airlines learned this the expensive way in 2022 when deferred system updates contributed to an $825 million loss and triggered a $1.3 billion “modernization” commitment.

We historically accepted these transfer costs because immediate human time felt more expensive than future human time. But when an AI agent can fix something in minutes that a human would need hours/days/weeks to context-switch into, the calculus flips. The cost of deferring often exceeds the cost of just doing it now.

The vocabulary of human time thinking

Once you start looking for it, human time thinking still shows up everywhere in how we talk about work.

PR feedback gets marked “non blocking”, “nit pick” or “nice to have later” because asking someone to address it now feels expensive. Refactoring discussions start with “is it worth it?” as if the answer depends entirely on labor cost. Scale and performance work gets pushed off because “we don’t have that problem yet,” which is another way of saying “we don’t want to spend human time on it yet.”

The classic advice “don’t prematurely optimize” made perfect sense when optimization meant days of profiling and careful restructuring. It makes less sense when an agent can run through common optimization patterns in an afternoon while you’re in meetings.

Even agents themselves perpetuate this framing. They give estimates in hours and days because they learned from documentation written by humans for humans. They’ll tell you a migration “should take about a week” when what they mean is “this would take a human about a week, but I could do it tonight.”

Parallelization changes everything

The constraint isn’t capacity anymore, it’s coordination.

An agent can work while you sleep, and multiple agents can run simultaneously on different parts of a problem. Wall clock time and human time have decoupled in ways our planning processes haven’t absorbed.

When I run four Claude Code instances in parallel on related parts of a codebase, the current bottleneck is merge conflicts and integration decisions. The work itself happens fast, but making sure the parallel streams cohere into something that actually functions together is where the time goes. This particular friction point will get solved as tooling catches up, but the broader pattern holds: every time agents get faster, the constraint shifts to whatever humans are still doing manually.

This is a fundamentally different dynamic than “we don’t have enough developer hours.” It requires different processes, different tooling, and different intuitions about what’s expensive and what’s cheap.

The API cost distraction

Teams obsess over and scrutinize API spend, optimize prompts to reduce token usage, and track inference costs down to the penny. This makes sense as line-item accounting (which is common in large organizations), but it misses the larger picture.

Inference costs are collapsing:

Epoch AI’s analysis shows prices falling 9x to 900x per year depending on performance level

The a16z LLMflation analysis found a 10x cost decrease annually for equivalent performance, faster than the PC revolution or dotcom bandwidth expansion

Stanford’s 2025 AI Index documented a 280-fold cost reduction for GPT-class models between 2020 and 2024.

Meanwhile, the costs we’re not measuring keep compounding: opportunity cost when deferred work blocks future features, coordination cost when context gets lost between deferrals, and risk cost when technical debt makes systems brittle in ways that only surface during incidents.

Measuring API spend while ignoring deferred work costs is like optimizing for gas mileage while ignoring that you’re driving in circles.

What actually changes

The tactical shifts are relatively straightforward once you accept the underlying premise.

For PR feedback, stop automatically ignoring anything marked “non-critical.” Low priority and nitpick comments become valid to fix immediately when agent time is cheap. You’re not asking a human to context-switch; you’re asking an agent to make a quick pass before the PR closes.

For backlog management, batch the “someday” items to an agent overnight. That pile of minor refactors and cleanup tasks that never quite makes it into a sprint? Let an agent work through it while you’re asleep. You might be surprised what’s feasible when the limiting factor isn’t human attention.

For estimation, challenge the implicit cost assumption in every “is it worth it?” question. The answer might have been “no” when it implied pulling someone off higher-priority work. It might be “yes” when it implies queuing something for an agent.

The cultural shifts run deeper. When someone asks "how long will this take?" we instinctively answer in human-hours, human-days, human-sprints. The entire grammar of estimation assumes human labor as the unit of cost. When agents work 24/7 in parallel, the complexity-to-cost relationship changes in ways that grammar wasn't designed to capture. I don't have a clean replacement yet, but I'm increasingly confident the current vocabulary will look as dated as waterfall diagrams within a few years.

The tooling gap

Our work tracking systems were designed for human workflows, and it shows.

Jira, Linear, GitHub Issues—all of them assume a human will pick up a ticket, work on it, and mark it done. None of them have good primitives for queuing work to agents, distinguishing what’s safe for autonomous handling versus what needs human judgment, or coordinating between multiple agents and humans asynchronously.

This is starting to change. Steve Yegge’s Beads project is exploring agent-optimized workflows. Tools like CrewAI, LangGraph, and AutoGen are building multi-agent orchestration patterns. Visual workflow builders like n8n and Dify are making it easier to design agent pipelines without writing custom code.

The patterns emerging include sequential handoffs, concurrent execution, maker-checker loops, and dynamic task building. These aren’t academic exercises but instead are responses to practical coordination problems that show up the moment you try to run lots of agents (and then nested sub-agents) on real work.

The villain is us

We are our own bottleneck here. We’ve internalized mental models based on constraints that no longer apply, and we keep reinforcing them in our documentation, our processes, and the training data we feed to agents.

The shift isn’t philosophical, it’s operational. Every time we ask “do we have bandwidth for this?” or “can we fit this in the sprint?” or “is this worth the engineering time?”, we’re applying a heuristic that made sense when human time was the binding constraint. When agent time is cheap and human time is better spent on judgment, taste and (some) orchestration, those questions need different answers.

The cost of inference is collapsing while the cost of deferred work compounds. The sooner our mental models catch up to that reality, the sooner we stop punting work that should just get done.